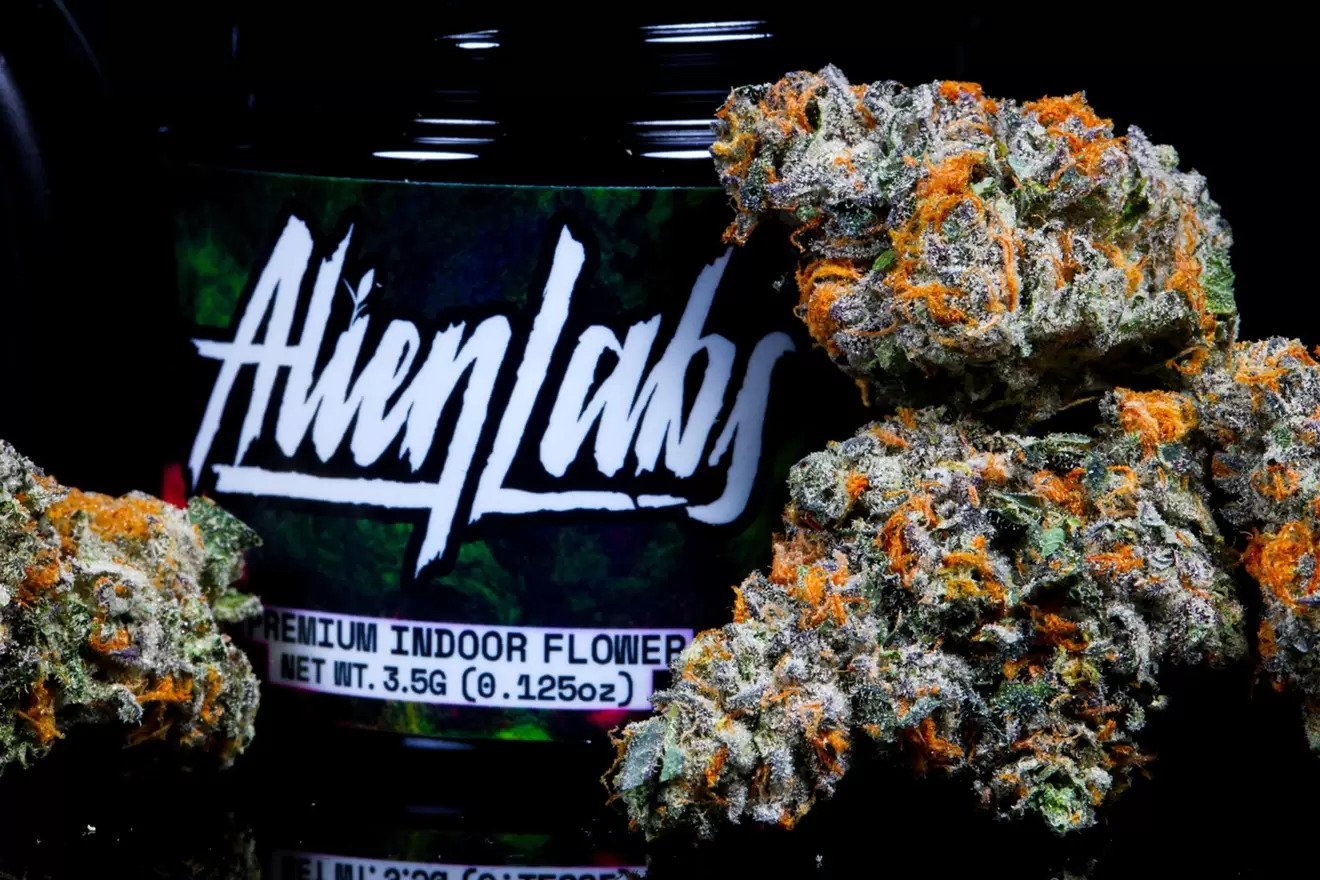

But what the film lacks in identity progress it more than makes up for in style. Having its bleak winter settings, its dark edges, and its disgustingly effective unique consequences, it looks and seems really good alien labs disposable.

My favorite picture is one in that the person, having only unmasked it self in scary fashion, scuttles around an unlucky scientist and melds with him. One of many results is a pointed mind, each half featuring the facial skin of an alternative person.

Hollywood. The land of glitz and style, of sparkle and sizzle; the “Hollywood” sign preening it self on a mountain overlooking the city, basking in the fantastic richness of its domain, which lies subjected just like the throat of a submissive dog. Where the abandoned sleep on the Hollywood Go of Recognition, tourists nudging them away to get a photo of Chuck Norris’s celebrity, waiting.

(He was guru in Missing in Action!) Nearby a madman shouts at an ATM device, that sympathetically beeps straight back, while still another group of tourists huddle around a celebrity, murmuring: Leslie Nielsen? Absolutely you aren’t significant? Critical indeed, significant as Erik Estrada’s celebrity residing in front of an anal lightening salon, the Spinctorium, only round the corner.

Hollywood. The graveyard of dreams. Where unemployed stars wait platforms in the neighborhood sushi shared, hoping for that large break, wanting to be discovered. To be plucked from this zoo of humanity, and elevated-into a movie star. Daily because they return home with their crowded residence, undiscovered, unimportant, an integral part of their desire dies, moving with a whimper.

Thirty years later, still waiting platforms in the same sushi restaurant, the desire is useless, just a vacant shell left out wondering me if I want some Nihonshu with my meal. If Disneyland, fifty miles to the south, is where dreams be realized, Hollywood will be its anus-the position dreams go to have flushed. Hope’s final resting stop.

Despite sharing the same title, The Thing is not a rebuilding of John Carpenter’s 1982 film. Or, for instance, could it be related to John Hawks’ 1951 film The Thing from Still another World. It is, actually, a prequel to Carpenter’s movie, occurring three times earlier and telling the story of the ill-fated Norwegian science team stationed in Antarctica.

Presented you’re common with this story, it doesn’t take a good jump of the creativity to figure out what happens. Carpenter’s movie began with men in a chopper firing at an Alaskan malamute that actually wasn’t a malamute but a shape-shifting unfamiliar person effective at absorbing and imitating other life types; this new film, on its most elementary terms, is all about how a person came to be a dog. I acknowledge that that seems very uninteresting, but there really is not any other way to place it.

It has its great amount of place out scares, while plenty of the suspense is lacking, in large part because there’s number true sense of mystery; there’s nothing about its character as well as its really existence that may shock us, mainly because Carpenter’s movie currently told us every thing we needed seriously to know.